The Drama of Being Human: What I’m still learning from Fr. Don Cozzens

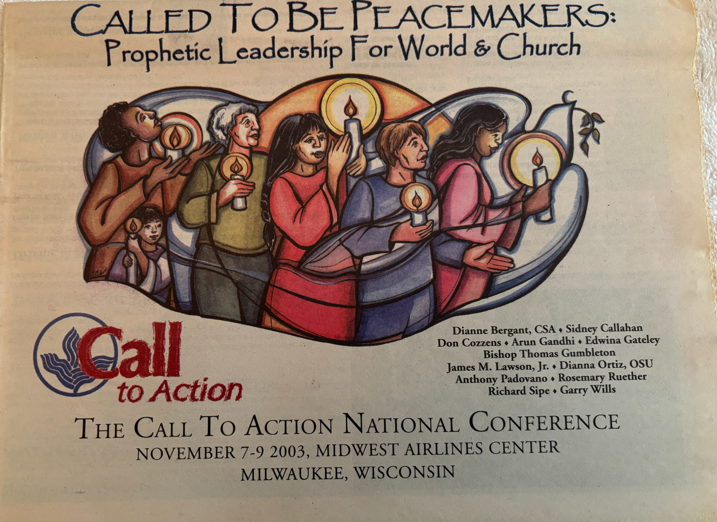

This piece originally ran in Commonweal. Fr. Cozzens was a longtime CTA member and national conference planner.

I can’t remember the first time I met Don Cozzens, because once you met him it was as if you’d always known him. Apple-cheeked, kind-eyed, Don radiated deep-seated friendliness and had a high-beam smile. I have not been among the devout who collect priests the way some collect prized antiques, knowing that they’ll cash in on the investment in a time of need. But when he became Writer in Residence at John Carroll University, his office was next to mine. We became friends.

By this time, he’d already published The Changing Face of the Priesthood in 2000 and become a national figure for his critique of the Church’s failure to deal with the priest sex-abuse scandal. But Don was an easygoing prophet who delighted in ordinary pleasures. He was particularly tempted by cafeteria fries and a good beer.

When the Church altered the language of the Mass in 2008, Don and I commiserated. The new translation seemed abstract, vaporizing the body. The priest used to greet the congregation, “The Lord be with you,” and we would reply, “and also with you.” Now we were to say, “and with your spirit.” As if our words were directed at the spirit alone, not the whole person. Don shared my consternation, noting now Jesus was said to take a “chalice,” which Don noted was a weirdly literalistic translation of calicem. A cup is so homely, so human. Like Don was.

I also missed the prayer before receiving communion: “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.” I loved that direct longing for total healing, the Roman centurion’s words to Jesus, asking him to heal his servant. The centurion’s humble faith touched Jesus. Now, it’s “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.” But what about our bodies?

I loved the fact that Don always spoke raptly about a girl he loved when he was in school, scandalizing and provoking the devout students in his Christian Sexuality class. Once, at lunch, Don was talking about the likelihood of priests being allowed to marry or whether women would be allowed to become priests, arguing that the former is far more likely to happen. A faculty member asked, “Are you telling me that priests will be allowed to have sex in my lifetime?” Don responded, “Your lifetime? It’s not about your lifetime. The question is, will they be allowed to have sex in my lifetime?!” He wanted priests to be able to be married, and did not believe celibacy should be mandatory. Celibacy, for him, was a charism for some people—including himself. But not everyone.

Around the time that the Church changed the language of the Mass, I began to suffer from excruciating back pain from a basketball injury. Shocks of pain radiated through my whole body. It got so bad I couldn’t sit down for more than a few minutes. All I could think about was my pain. I wanted to be healed. Only say the word, I kept saying under my breath, even as everyone around me repeated the new translation, and I shall be healed. Saying that prayer felt like a balm.

Don was an easygoing prophet who delighted in ordinary pleasures.

At the end of a day at work, aching, I’d hobble home through the rec center and past the courts. I had to turn away or my pain would double. The thought that I couldn’t be out there was too much to bear. One day, I decided to visit Don, and the pain poured out of me. Don listened, sitting with me and my suffering. I felt as if I were being punished by God. But Don replied, “It is often said that God loves you. But I believe that God likes you as well.”

Don helped me to imagine a God who took pleasure in me—not a God of judging love, but one who delighted in me, and also suffered with me. To imagine a God who likes us, even now, feels like a gift. A God who wants to hang out with us and feast with us, but also hear us in our pain.

This is at the heart of the Christian mystery, a story that cannot be entirely explained but must be lived into: that God chose to inhabit the flesh to feel our delights and pain, to enter into the drama of being human. And not simply to walk around preaching and healing, but also to relish a good meal with friends, as Don did just before his death from Covid in 2021.

In my pain and doubt, I’ve often questioned whether there is a God. But if there is, then Don was one of God’s messengers. Though Don was a prophet, he did not delight in criticizing the Church. He devoted his life to that Church. For him, as he wrote in his 2013 book Notes from the Underground, it “has the right to be sick, to be broken and wounded. It’s human after all…. But the Church doesn’t have the right to turn the freedom and light of the Gospel into a closed system entrenched in a medieval, feudal, and fortified castle.” His Church was a pilgrimage, not a fortress. Not a place, but a journeying together of “pilgrim people.”

After Masses, Don would head with students to a local pub, asking them about their lives and their faith journeys. He was a living embodiment of the listening Church. He taught courses on the theology of love and sex, on Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day—the Church of communion, of abiding with the poor, the marginalized, the forsaken. He spoke often of the essential place of women in the Church and its need for their full inclusion.

Sadly, some people felt Don was attacking the Church itself. During the homily of Don’s funeral Mass, Fr. Tom Moloney lamented that “[Don] was not only ignored by many of the Cleveland priests and seminarians—he was rejected and shunned…. He was deeply saddened and hurt by the response.”

Sometimes, when I walk past the racquetball court, I remember Don there, whacking away one of his unhittable serves. Though his knees ached, at age eighty, he still wanted to play.

We walk through life in our tender flesh for such a brief time, relishing in its pleasures and suffering its pains. We take it all together, the delight and the hurting, or we take it not at all. In the end, we will all be broken. The hope is that we will be broken open and received into the fullness of God.

Maybe the Church is like that too. Pope Francis famously called the Church a field hospital, a temporary place where the wounded can find care and healing. That’s what Don believed as well, even if he also believed that the Church needed to heal itself, too.

Philip Metres is a professor of English at John Carroll University, where he also directs the Peace, Justice and Human Rights Program and the JCU Young Writers Workshop. His most recent book of poetry is Fugitive/Refuge (Copper Canyon Press). Find him at philipmetres.com